Urban Agriculture - Justification and Planning

Published by City Farmer, Canada's Office of

Urban Agriculture

Urban Agriculture -

Justification and

Planning Guidelines

Urban Vegetable Promotion Project

By

Petra Jacobi,

Axel W. Drescher and

Jörg Amend

Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives (MAC)

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ)

Dar es Salaam/ Freiburg

May, 2000

Urban Vegetable Promotion Project

P.O.Box 31311,

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

e-mail:uvpp@africaonline.co.tz

Tel: 051-700947, 0812-784033

Urban Agriculture - Justification and Planning Guidelines

Table of Content

List of Abbreviations

Background of the study

1 What is Urban Agriculture and who are the people doing it?

1.1 Defining Urban Agriculture

1.2 The urban farmers

2 Urban food production - A result of crisis

3 The crisis model - assessing the potential of Urban Agriculture

3.1 Preconditions

3.2 Supporting factors for Urban Agriculture

4 Analysis of Urban Agriculture case Studies

4.1 The source - Urban Agriculture case studies

4.2 Comparing the case studies

4.2.1 Urbanisation and poverty levels

4.2.2 Farming Systems Information

4.23 Basic conditions and requirements for urban agriculture

4.2.4 Conditions and requirements for improved performance of urban agriculture

5 Supporting Urban Agriculture - what can interventions look like ?

5.1 The areas of interventions

5.2 Roles and functions within the intervention areas

5.2.1 Research

5.2.2 Policy

5.2.3 Action

5.3 Cross-cutting issues

5.4 The Urban Agriculture flow chart

6 Urban Agriculture in the current development discussion and recent initiatives

7 Outlook

8 References

Annex

Annex 1 List of city case studies and reference persons

Annex 2 Main climatic conditions of selected cities

Annex 3 Basic conditions and requirements for urban agriculture

Annex 4 Conditions and requirements for improved performance of urban agriculture

List of Tables

Table 1 Population growth, informal employment and poverty in selected countries of

Africa, Latin America and Asia

Table 2 City and location of main agricultural activities - farming systems information

Table 3 Basic conditions and requirements for Urban Agriculture

Table 4 Conditions and requirements for improved performance

Table 5 Possible areas for the integration of Urban Agriculture as an intervention

List of Figures

Figure 1 Conditions for the development of Urban Agriculture as a response to crisis

Figure 2 Improved performance of Urban Agriculture

Figure 3 Major factors supporting the improved occurrence of Urban Agriculture

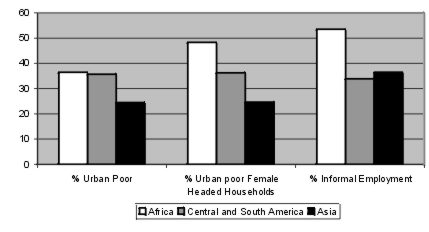

Figure 4 Urban Poverty and informal sector employment in Africa, Central and South

America and Asia

Figure 5 The phenomena Urban Agriculture and its temporal sequence

Figure 6 Urban Agriculture Interventions

List of Abbreviations

| ACPA | Cuban Association of Urban Livestock Farmers |

| AGUILA | Agricultura in Latino America |

| BMZ | Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung - German Federal Ministry for Co-operation |

| CTA | EU Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Co-operation |

| DANIDA | Danish International Development Assistance |

| DSE | Deutsche Stiftung für Internationale Entwicklung - German Foundation for International Development |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organisation |

| FAO-COAG | FAO Committee on Agriculture |

| GTZ | Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit - German Development Co-operation |

| IDRC | International Development Research Centre |

| IFPRI | International Food Policy Research Institute |

| SAP | Structural Adjustment Programme |

| SIDA | Swedish International Development Co-operation Agency |

| SGUA | Support Group of Urban Agriculture |

| TUAN | The Urban Agriculture Network |

| UA | Urban Agriculture |

| UNCHS | United Nations Centre for Human Settlement |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNEP | United Nations Environmental Programme |

| WB | World Bank |

| WFP | World Food Programme |

| WIR | World Resource Institute |

Background of the study

by Petra Jacobi, Axel W. Drescher and Jörg Amend

One of the biggest challenges of the next decade facing mankind is the growing population and increasing urbanisation. The world's current population of 6 billion is equally shared between cities and rural areas, with urban areas expected to surpass rural areas in population around the year 2005 (FAO 1998).

In developing countries the capacity of governments to manage this urban growth is threatened and in many countries is already on the decline. The creation of "sustainable cities" and the identification of ways to provide food, shelter and basic services to the city residents is a challenge to many city authorities around the world.

This paper is therefore targeting institutions and individuals confronted with the task of initiating sustainable urban development, especially in developing countries. These decision-makers are faced with complex and often difficult frame-conditions. Their task is to develop strategies to cope with them.

The authors will highlight one strategy, which is used by the urban people themselves and today witnessed in many cities throughout the world - Involvement in Urban Agriculture (UA). We want to show that planned and guided support of urban agriculture can be an effective tool to buffer hardships for vulnerable urban groups and create a better urban habitat.

The paper will cover the following aspects:

- What is understood by Urban Agriculture and who are the people doing it?

- We will show that Urban Agriculture activities in many cases are linked with economic crisis and a reaction of urban residents to cope with it.

- By looking at the factors under which urban agriculture evolves we get an indication of when Urban Agriculture is considered effective by the urban residents themselves. When is UA a worthwhile preventive measure to buffer urban poverty in a city?

- This frame is supported by a comparison of experiences from different cities in Africa, Asia and South America. How does UA look elsewhere?

- We want to share some ideas on what effective support to urban agriculture can look like. What are the crucial activities that need to be supported by city authorities?

- Finally we will place support of UA in the current development discussion. Where does it fit?

The study is based on the experiences of the Urban Vegetable Promotion Project*[The Urban Vegetable Promotion Project (UVPP) was launched 1993 as a bilateral project between the the Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives (MAC) and the German Development Co-operation (GTZ). It is financed by the Ministry of Economic Co-operation (BMZ).]) in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) and draws additional information extracted from 20 papers on city case studies on urban agriculture world-wide (see Annex 1 for details). Most of these case studies were commissioned by the German Development Co-operation (GTZ) in 1998/1999 and presented in an International Workshop in Havana, Cuba, organised by the German Foundation for International Development (DSE), the Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Co-operation (CTA), the Swedish International Development Co-operation Agency (SIDA) and the Cuban Association of Urban Livestock Farmers (ACPA) in Havana, Cuba in October 1999. Additional literature and own experiences of the authors in urban agriculture will complement the information.

1 What is Urban Agriculture and who are the people doing it?

1.1 Defining Urban Agriculture

UNDP (1996) defines urban agriculture as follows: "Urban Agriculture (UA) is an activity that produces, processes, and markets food and other products, on land and water in urban and peri-urban areas, applying intensive production methods, and (re)using natural resources and urban wastes, to yield a diversity of crops and livestock".

Accounting for the broader needs of the urban population, FAO-COAG (1999) states that: "Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture are agriculture practices within and around cities which compete for resources (land, water, energy, labour) that could also serve other purposes to satisfy the requirements of the urban population. Important sectors of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture include horticulture, livestock, fodder and milk production, aquaculture, and forestry."

A more integrated definition is given by Mougeot (1999): "Urban Agriculture is an industry located within (intra-urban) or on the fringe (peri-urban) of a town, an urban centre, a city or metropolis, which grows or raises, processes and distributes a diversity of food and non-food products, reusing mainly human and material resources, products and services found in and around that urban area, and in turn supplying human and material resources, products and services largely to that urban area".

Urban food production is practised by large parts of the urban population in developing countries, and it appears in various forms. In this wider sense Urban Agriculture refers not only to food crops and fruit trees grown in cities but encompasses different kind of livestock as well as medicinal plants and ornamentals for other purposes.

A broad understanding of urban agriculture must take into account the various activities of households to achieve food security, and to create income. Urban food production is more than food related. Community-based and individual food production in cities meets further needs of the urban population like sustainable urban development and environmental protection (FAO-COAG 1999, IFPRI 1998, TUAN 1994).

1.2 The urban farmers

The urban farmers are women and men coming from all income groups, but the majority of them are low-medium income earners, who grow food for self-consumption or as income generation. Most of the cultivation is informal with little if any support.

Women tend to dominate certain components of urban cultivation (backyard gardening, small scale animal husbandry). Women are still disadvantage in the formal sector of the urban economy and therefore get involved in small- and micro-scale production. Urban food production offers opportunities to be integrated into other household activities and women uphold the responsibility for household food security. Men tend to dominate the commercial urban food production. In some countries children are involved mainly in weeding and watering. Different urban farmers engaged in different production systems co-operate with one another: they may use each others plots for different purposes at different times and they exchange wastes or products (Mougeot 1999).

Urban agriculture links farm cultivation with small scale enterprises, such as street food stands, fresh milk outlets and maize roasters (FAO-COAG 1999) but also to fencing industry, pumping, irrigation, processing and transportation industries.

2 Urban food production - a result of crisis?

Urbanisation is one of the major issues facing mankind today and is in its extent unique in world history. Neither international government bodies nor national or local governments are well prepared to deal appropriately with this development but none of them can afford to ignore this phenomenon. Recent surveys suggest that the locus of poverty is shifting to urban areas (Haddad et al. 1998), making food insecurity and malnutrition urban as well as rural problems. In 1988, about 25% of the developing world's absolute poor were living in urban areas; by 2000, 56% of the absolute poor will be living there (WRI 1997). Malnutrition in the poorest areas of cities often rivals that found in rural areas (IFPRI 1998a). Many decision makers in the world's cities are today confronted with this development of increasing urban poverty.

The impact of globally induced crisis and their effects on regional level are reasons (global reasons) why urban poor face worsening conditions (recently experienced by Asia). The burdens imposed on consumers by structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) can add to the pressure (Drescher & Iaquinta 1999, Foeken & Mwangi 2000, Hasna 1998, Mbiba 2000 and others).

Market liberalisation either reinforced by SAPs or national governments typically include and directly affect national economies and local livelihood conditions through:

- export-oriented market reforms that raise basic commodity prices,

- currency devaluation that increase import prices, and

- cuts in food subsidies for urban consumers.

The short- and medium-term results of conditional programs have put an economic squeeze on poor populations in developing countries who frequently resort to non-market (informal sector) activities for survival. Of additional concern for the households are:

- decreasing stability and security in formal sector employment

- a decline in the real wages of urban workers

- blurring of the distinction between formal and informal sectors

- narrowing of the income gap between rural and urban dwellers, and

- accelerated migration from rural to urban areas (Nugent 1997).

Rapid population growth in cities is caused by in-migration of rural people in cities but also by population growth in the cities themselves. For many cities in the South, this can mean a yearly population growth of 60-70,000 people or more. Unemployment, gradual break down of basic civil services (water supply, food supply, housing, health care, schools, transport, market facilities, waste management) and lack of food are consequences of this development. Population density is another consequence of population growth and missing urban planning. This situation is less a sudden development, but more a "permanent crisis".

Globally induced economic crisis, rapid population growth and migration, deteriorating national economies or persisting economic difficulties are the cause for urban food production in many developing countries. Nevertheless urban food production would have less importance by far if there were not a shortage of adequate and accessible income opportunities and an unsatisfied demand for appropriate quantity and quality of agricultural products in cities on local level (see city case studies).

Urban food production is in many cases a response of urban poor to:

- inadequate, unreliable and irregular access to food supplies, due to either a lack of availability or a lack of purchasing power *[Unreliable and irregular access can be caused by natural disasters (hurricanes George and Mitch in 1999) or economic disasters (recent strikes in Ecuador, causing food shortages for several days).])

- inadequate access to formal employment opportunities, due to deteriorating national economies in developing countries.An additional reason for the involvement in Urban Agriculture is the:

- desire for a better habitat

e.g. leisure/ personal satisfaction or green cities (e.g. maintaining open spaces), waste management, composting (overall vision).

However the latter is more prominent for those groups who have already satisfied their basic needs or for decision makers and town-planners as it indicates a vision for the city as a habitat (Sawio 1998, van der Bliek 1996). Focussing on the first objectives, urban food production can be seen as a "crisis strategy", ensuring survival of the poorer segment of the population.

Supporting the "crisis model" view, are examples of people's survival strategies during periods of economic decline and social unrest in densely populated cities like Jakarta and Ulan Bator.

Jakarta is one example in recent history. The economic turmoil that first hit Indonesia in 1997 has left millions of people vulnerable to food insecurity, without enough money to buy sufficient food. First urban areas were dramatically affected. Alarming food related problems were reported (FAO 1999a). As a reaction to this people started to produce food on small plots and open spaces all over the city--even transformed former public parks into gardens and government bodies encouraged the people of Jakarta to grow their own food. Problems started in urban areas to spread to rural areas later, caused by migration. In some rural communities the population has increased up to 30%, putting severe pressure on those areas (FAO 1999a).

Maidar (1996) reports an example from Mongolia. The recent "shock therapy" measures taken by the Government have created great hardship as prices for consumer goods rise while salaries remain unchanged. The prices for food, coal, wood, electricity, transportation, etc. are skyrocketing. In 1990/1991, 850 families grew vegetables in the city. In 1996 this number has increased over 20 times reaching 21,000. More and more families have begun to realise that urban agriculture might be a way to improve their standard of living.

Urban Agriculture is emerging strongly in Sub-Saharan Africa, where the fastest urban growth will occur in countries least equipped to feed their cities (Ratta & Nasr 1999).

Increasing farming activities in cities are closely linked to economic decline and increasing poverty in urban centres. This is the case for many African cities but also for Latin America and Asia. Several case studies report on the importance of urban food production for home consumption and income generation as a response to crisis.

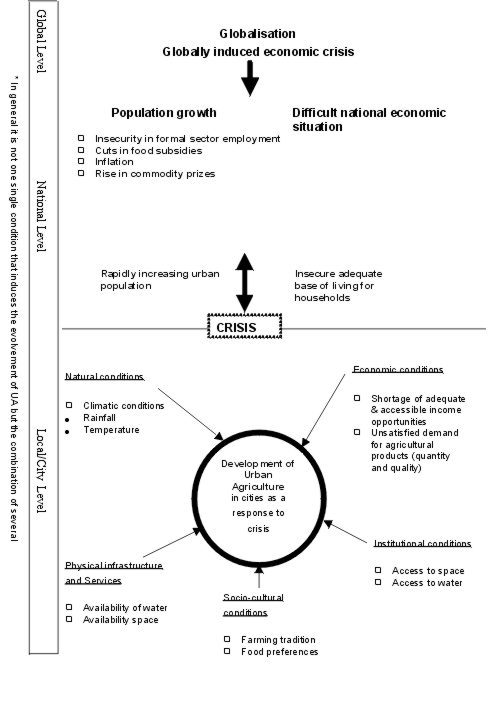

3 The crisis model - assessing the potential of Urban Agriculture as strategy against urban poverty

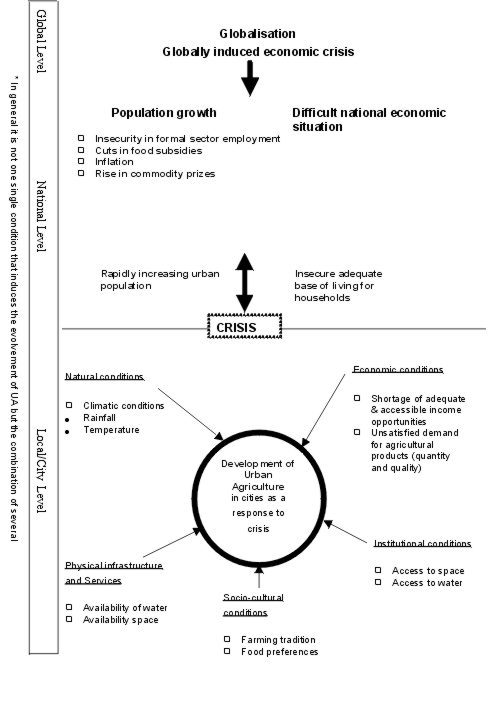

Involvement in Urban Agriculture has been introduced as a strategy used by the poorer urban population to cope with crisis (Jacobi, 1998), however not all cities in the developing world show the same degree of agricultural activities. Urban Agriculture and consequently the effect it can have on the living standard of the urban households depends on a variety of factors and even more their combination. The crisis Model (figure 1) combines major factors influencing the rise of UA on the global and national level as well as the basic conditions necessary on a local/city level.

Basic factors or preconditions are those, which are essential for the "consideration" of Urban Agriculture as a survival strategy, they have to be met to allow UA. The model does not give preference or a value to an individual factor, as they have to be looked at in a systemic way. A certain favourable combination of some can compensate shortcomings in other fields. Most areas are self-explanatory, either natural, socio-cultural, institutional or economic conditions or related to physical infrastructure and services.

Decision makers and urban planners have to assess these factors in their city and decide which role UA can and maybe should play. Often this is a matter of available alternatives. Various factors can be actively influenced. Depending on the efforts which have to be undertaken UA is a very economic strategy to fight urban poverty and improve sustainable city development.

3.1 Basic factors or preconditions

Agricultural activities in a given city require basic conditions. Five major areas determine the occurrence of urban agriculture:

- natural conditions;

- physical infrastructure and services;

- socio-cultural conditions;

- institutional conditions; and

- economic conditions.

Natural Conditions

Climatic conditions (amount and seasonality of rainfall and temperature) determine urban food production. Very low annual rainfall, for example in Cairo or Lima (25 mm) is restrictive to the development of urban crop and vegetable production but can offer opportunities for animal husbandry. In areas with favourable climatic conditions we expect higher occurrence of Urban Agriculture, because no major investments are necessary to start production, which makes it an option for all income groups.

Physical infrastructure and services

Basic requirements for production are the availability of water and space. If either one or both are not available households can not respond to crisis by entering into any kind of production. The availability of infrastructure for water coupled with access (here referred to as institutional condition) to water can compensate for lack of rainfall and, in spite of this, lead to Urban Agriculture. If Urban Agriculture is dependent on infrastructure UA will be dominated by certain groups having access to it and most likely more economic oriented.

Socio-cultural conditions

This refers to the households farming traditions and food preferences as an entry point into urban agriculture and indicates that urban agriculture is not a completely unknown and unskilled activity in many cases. Urban Agriculture is easily started by groups who culturally have a farming background. Food preferences are related to specific types of vegetables and other agricultural produce, often local varieties, which are not marketable or not available on local markets and therefore produced on household basis.

Institutional conditions

Here identified as the capability of institutions to provide or at least not restrict access to water and space. Access to water and space is reported to be a social and institutional problem, often gender specific. Access to water and space can sometimes be influenced through law and proper land use planning.

Institutional conditions have to be linked with the legal framework for urban production. In cases where the legal framework is restrictive weakness of institutions will favour UA, but make it an illegal activity.

Economic conditions

Refers to the urban labour market and the shortage of adequate and accessible income opportunities and an unsatisfied demand for agricultural products in quantity and quality. The question of employment opportunities is self-explaining if we consider population growth rates of 5-8% in many cities. More than 250.000 new jobs each year are needed in Jakarta, more than 77.000 new jobs in Ouagadougou, and in Dar es Salaam there is a demand for more than 44.000 jobs each year only to keep the unemployment rate at a similar level as today (Nugent 1999). Therefore people are forced to enter into informal jobs, like urban agriculture to gain income.

Poor rural-urban infrastructure and/ or high transport costs generally favour the production of perishable products (e.g. leafy vegetables, milk and milk products) when they are integral parts of the human consumption.

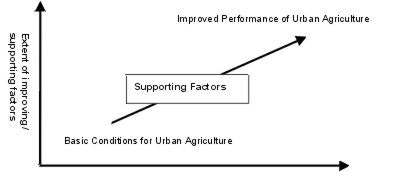

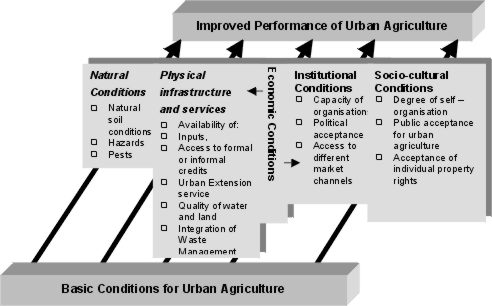

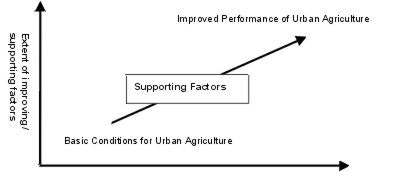

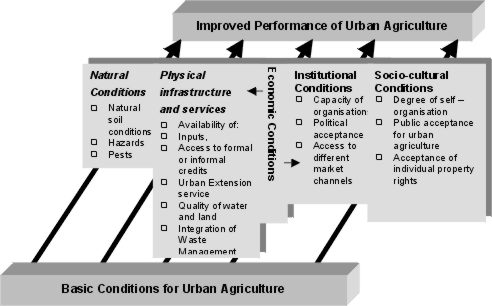

3.2 Supporting factors for of Urban Agriculture

The "supporting" factors give an indication about the "quality" or " performance" of agricultural activities in a city. They make it easier for people to get involved in it and raise its preference as a survival strategy against other alternatives. This means: more UA activities in the city, higher yield potentials, better management & food safety and higher degree of integration into other urban issues (figure 2 & 3). In many cases it indicates the shift of UA being an informal, partly illegal activity to an accepted legal income opportunity. Most of the supporting factors can be actively influenced and indicate possible areas of interventions. We refer to the same areas as used in figure 1.

Figure 1 Conditions for the development of Urban Agriculture as a response to crisis

Figure 2: Improved Performance of Urban Agriculture

Most of the supporting factors can be actively influenced and indicate possible areas of interventions. We refer to the same areas as already mentioned (Figure 1).

Natural conditions refer to soil conditions/ climatic conditions (microclimate) that favour agriculture. Good yields and lower expenditure for fertilisers and irrigation, but also low pest and diseases pressure and limited natural hazards (flooding, storm etc.) can strongly favour UA. Favourable conditions reduce risks and the need for up-front investment to get started and make it an option for many income groups.

Physical infrastructure and services: The availability of inputs, access to formal or informal credit , urban extension services are important aspects. The quality of water and land refers to the general suitability for agricultural use (usability), but also to the influence infrastructure can have on the value of production plots (e.g. availability of tap water, fenced and therefore secure plots, drainage). Urban Agriculture can benefit if it is incorporated in urban nutrient recycling (organic waste management in cities) (Furedy et al. 1997; IDRC 1999; Kiango & Amend 1999).

Figure 3: Major factors supporting the improved occurrence of urban agriculture

Economic conditions which are linked with physical infrastructure (availability of inputs, e.g. shops which sell seeds, tools etc.), and the farmers access to formal or informal credits and saving schemes. On the other hand the availability of and the access to different market channels is closely related to economic conditions. A major constraint of many urban small scale producers is the lack of selling opportunities.

Institutional conditions refer to the capacity of organisations to adequately fulfil their mandates but also the political acceptance of Urban Agriculture. The latter is reflected in permissive or supportive laws for Urban Agriculture (Quon 1999), while the first one refers more the to implementation side of existing legislation and to efficient delivery of services. Proper functioning of institutions would for example have influence on water supply to communities, allocation and use of land, better integration of waste recycling and environmental protection in city development.

Socio-cultural conditions that influence Urban Agriculture are the degree of self-organisation of urban residents and in our case farmers (e.g. the formation of user-groups, co-operatives, associations). A clear articulation of demand towards decision-makers is linked with the organisational capacity of the farmers. This needs to be strengthened (Jacobi et al. 2000). Public acceptance of Urban Agriculture, which is in some areas closely related to farming traditions, in other regions probably more to the issue of sustainable city development and degree of awareness on food quality is seen as another favouring condition. Acceptance of individual property rights, which relates to the observation, that urban agricultural produce is very often subject to theft (Drescher 1998), A high degree of acceptance of property would such increase readiness to cultivate.

4 Analysis of Urban Agriculture case studies and regional comparison

4.1 The source - Urban Agriculture case studies

It is our opinion that crisis situations in many countries of the developing world make people turn to UA. We have highlighted certain factors which determine its expression.

In a next step we are looking at these factors in various cities world-wide and trying to elaborate differences and mutualities. Information is drawn from 20 urban agriculture case studies, which mostly have been commissioned by the German Development Co-operation (GTZ) in 1998/1999 and presented in an International Workshop in Cuba 1999 (see Annex 1).

The case studies describe the reality of urban agriculture in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Basic information is summarised and highlighted in Tables 1 and 2. More detailed information is presented in the Annex.

All case studies describe the common production systems in urban and peri-urban areas. We realised, that the documented case studies are very incoherent. They are written by people with different professional backgrounds, emphasising various issues. They vary greatly in their methodology, data quality and use, inter-sectoral linkage, disciplines involved and policy or action orientation. It again reflects the complexity of UA and also hints at the problems to describe the phenomena in a linear way.

Table 1: Population growth, informal employment and poverty in selected countries of Africa, Latin America and Asia

|

Country |

Urban Population

(in 1000) |

Population Growth Rate (percent) |

Informal Employment |

Poor Households |

Poor Households (Female Headed) |

|

|

|

|

|

Urban |

|

|

Rural |

|

(percent) |

(percent) |

(percent) |

|

1980 |

2000 |

2020 |

1980-85 |

2000-05 |

2020-25 |

1980-85 |

2000-05 |

2020-25 |

1993 |

1993 |

1993 |

|

Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Angola |

1,467 |

4,371 |

10,697 |

5,6 |

4,9 |

3,8 |

1,9 |

2,0 |

1,2 |

36 |

36 |

41 |

|

Botswana |

137 |

1,191 |

2,142 |

13,7 |

4,2 |

1,6 |

0,9 |

-5,5 |

0,2 |

45 |

55 |

40 |

|

D.R.Congo |

7,756 |

15,67 |

39,648 |

2,7 |

4,5 |

4,1 |

3,4 |

2,3 |

1,4 |

50 |

48 |

80 |

|

Egypt |

19,178 |

31,297 |

51,098 |

2,6 |

2,6 |

2,1 |

2,6 |

1,0 |

-0,2 |

x |

43 |

x |

|

Ghana |

3,368 |

7,644 |

16,742 |

4,2 |

4,2 |

3,2 |

3,1 |

1,7 |

0,7 |

70 |

25 |

x |

|

Kenya |

2,673 |

10,043 |

22,468 |

7,7 |

5 |

3,4 |

2,0 |

1,3 |

0,8 |

52 |

27 |

25 |

|

Lesotho |

183 |

641 |

1,544 |

6,8 |

5,1 |

3,4 |

2,0 |

1,3 |

0,8 |

31 |

49 |

59 |

|

Malawi |

565 |

1,686 |

4,657 |

5,8 |

5,2 |

4,5 |

2,9 |

2,0 |

1,4 |

51 |

66 |

x |

|

Nigeria |

19,353 |

56,651 |

124,888 |

5,5 |

4,6 |

3,0 |

1,8 |

1,2 |

0,8 |

77 |

62 |

67 |

|

Senegal |

1,988 |

4,463 |

9,09 |

3,9 |

4 |

2,8 |

2,2 |

1,3 |

0,6 |

47 |

13 |

x |

|

South Africa |

14,043 |

23,291 |

39,548 |

2,6 |

2,7 |

2,2 |

2,4 |

1,5 |

0,0 |

x |

x |

x |

|

Tanzania |

2,741 |

9,376 |

23,354 |

6,7 |

5,2 |

3,7 |

2,5 |

1,7 |

1,0 |

x |

23 |

x |

|

Togo |

599 |

1,556 |

3,589 |

5,9 |

4,3 |

3,6 |

2,0 |

1,8 |

1,0 |

27 |

12 |

x |

|

Uganda |

1,154 |

3,18 |

9,333 |

4,8 |

5,5 |

4,8 |

2,1 |

2,5 |

1,7 |

46 |

77 |

36 |

|

Zambia |

2,285 |

4,067 |

8,019 |

2,8 |

3,3 |

2,9 |

1,8 |

1,8 |

0,6 |

x |

17 |

69 |

|

Zimbabwe |

1,587 |

4,387 |

8,928 |

5,8 |

4,1 |

2,5 |

2,5 |

1,0 |

0,0 |

17 |

x |

x |

|

Europe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bulgaria |

5,42 |

5,82 |

5,867 |

1,3 |

0,0 |

-0,1 |

-1,6 |

-1,7 |

-1,8 |

12 |

x |

|

|

America |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Costa Rica |

985 |

1,97 |

3,308 |

3,7 |

2,9 |

2,0 |

2,3 |

0,7 |

-0,1 |

x |

24* |

|

|

Cuba |

6,613 |

8,727 |

9,838 |

1,7 |

0,8 |

0,3 |

-1,1 |

-1,4 |

-1,2 |

x |

x |

x |

|

Haiti |

1,269 |

2,727 |

5,471 |

3,7 |

3,6 |

3,1 |

1,2 |

0,8 |

0,6 |

x |

65* |

|

|

Dominican Rep. |

2,877 |

5,537 |

8,013 |

3,8 |

2,3 |

1,2 |

0,5 |

-0,3 |

-0,6 |

x |

45* |

|

|

Mexico |

44,832 |

73,553 |

99,069 |

3,2 |

1,7 |

1,2 |

0,2 |

0,6 |

-0,5 |

x |

23* |

|

|

Brazil |

80,589 |

137,527 |

182,139 |

3,4 |

1,7 |

0,9 |

-0,7 |

-1,4 |

-0,6 |

36 |

19 |

22 |

|

Peru |

11,187 |

18,674 |

26,778 |

3,1 |

2,1 |

1,4 |

1,0 |

0,2 |

-0,3 |

49 |

29 |

7 |

|

Asia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

China |

195,908 |

438,236 |

711,698 |

4,2 |

2,9 |

1,7 |

0,6 |

-0,6 |

-0,8 |

x |

9* total Popul. |

x |

|

India |

158,851 |

186,323 |

498,777 |

3,2 |

2,9 |

2,5 |

1,8 |

0,9 |

-0,2 |

67 |

17 |

14 |

|

Laos |

429 |

1,336 |

3,361 |

5,4 |

5,2 |

3,5 |

1,8 |

2,0 |

0,7 |

x |

24 |

x |

|

Philippines |

18,11 |

43,985 |

69,862 |

5,2 |

3,1 |

1,6 |

0,6 |

-0,1 |

-0,4 |

20 |

13 |

9 |

|

Vietnam |

10,338 |

15,891 |

28,439 |

2,5 |

2,4 |

3,3 |

2,1 |

1,3 |

0,2 |

x |

51 |

x |

|

Source: World Resource Institute 1998-1999, p 274 ff. *Data for 1980-1990 by World Resource Institute 1996-1997, p 150 ff., x = no data available |

4.2 Comparing the case studies

4.21 Urbanisation and poverty levels

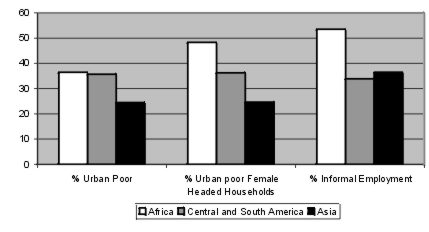

Comparing the economic conditions in cities of Africa, Latin America and Asia with respect to population growth, percentages of urban poor households and informal sector employment, the following is obvious:

- Urban population growth rate is at present highest in Africa. Urbanisation here has only recently started while in Asia it is still in full swing and in South America it is nearly completed.

- Urban poverty is prevalent in Africa (36,5%, n=33 cities) and Central and South America (35,7%, n=7), while in Asia 24,5% of urban household belong to the poor (n = 12).

- According to data of WRI (1999) female headed poor urban households are most frequent in Africa (48,3 %, n=17), while in Central and South America 36,2% (n=15) and in Asia 24,6% (n=12) of this category belong to the poor.*)

- The strongest development of the informal sector employment can be observed in Africa (53,5%; n=30), followed by Asia with 36,5% (n=26) and Central and South America with 33,9% (n=14)

Figure 4: Urban Poverty and Informal sector employment in Africa, Central and South America and Asia (Source: Data of WRI, 1997/1999)

Table 2: City and location of main agricultural activities - farming systems information

|

City

|

Urban Area |

Peri-urban Area |

Average Farm (Plot) Size |

Gender Specificy |

|

Africa |

|

|

|

|

|

Accra (Ghana)

|

Food crops, home gardens: vegetables, poultry

Open spaces: crops, vegetables |

Crop farming, mixed farming

|

No data

|

PU5): Men (vegetables)

U6): Men (crops)

Women (small livestock) |

|

Nairobi (Kenya)

|

Home gardens, vegetables, poultry

Open spaces |

Market farms, crops, poultry, livestock |

No data |

U: Women PU: |

|

Dakar (Senegal)

|

Home gardens: vegetables

Small scale livestock (poultry, sheep) |

Vegetables, battery chicken, laying hens |

U: 10-30 m_

PU: 0,1 - 1,0 ha (small-scale); 1 - 20 ha (market) |

PU: Men

U: Women (98% home gardens) and men |

|

Dar es Salaam (Tanzania)

|

Home gardens, community gardens, small-scale livestock

Open space: vegetables |

Vegetables, mixed crop-livestock system

fruit production |

PU: 2 ha

U: few m_ to some 100 m_ (Home gardens)

U: 700-950 m_ (open spaces) |

PU: Men and Women

U home gardens: Women

U open spaces: Men and women |

|

Kampala (Uganda)

|

Open spaces: crops, vegetables, poultry |

|

PU: 1200 m_

U: 100 - 400 m_ |

U: Women |

|

Lusaka (Zambia)

|

Home gardens, small scale livestock

Open space: crops and vegetables (rainy season) |

Vegetables and crops, livestock

|

PU: 830 m_ (small scale)

U: 120 m_ (gardens, high density); open space: 420 m_ |

PU and open spaces: Men

U: home gardens: Women |

|

Harare (Zimbabwe)

|

Home gardens, vegetables, small livestock

Open space: crops (rainy season) |

Market horticulture vegetables, crops, livestock |

PU: 430 m_

U: 30 m_ - 300 m_ (high density - low density)) |

PU: Men (large scale market) Women (small scale market)

U: Women |

|

Europe |

|

|

|

|

|

Sofia (Bulgaria) |

Home gardens , vegetables

Private commercial farms |

Crops, livestock (private) |

U: 1000 - 10 000 m_ |

U: Women |

|

Latin America |

|

|

|

|

|

San Jose (Costa Rica) 1) |

Home gardens: vegetables |

Vegetables |

U: 20 - 100 m_

PU: 100 - 2700 m_ |

U: 90% women (home gardens) |

|

Havana (Cuba) |

Community orchards, organoponics: vegetables, spices, medicinal plants |

Organoponics, poultry, fruits, |

U: 1200 m__

PU: |

U and PU: men and women |

|

Continued Table 2: Latin America |

|

City |

Urban Area |

Peri-urban Area

|

Average Farm (Plot) Size |

Gender Specifics |

|

Latin America |

|

Santiago (Dominican Republic) 2) |

Solares (plots): food crops, tobacco, small scale livestock

Home gardens: vegetables |

Food crops, tobacco, livestock |

U: 200-600 m_

PU : ca. 2 ha |

U: men (crops), women (small scale livestock, home gardens)

PU: dito 2) |

|

Port-au-Prince (Haiti)3) |

Home gardens: Ornamentals, vegetables, medicinal plants crops, trees |

Open spaces: crops, vegetables, trees, ornamentals, |

U: 5 m_ - 1 ha

PU: 100 m_ - 25 ha and more |

U: Women and men

PU: Men and women |

|

Mexico City (Mexico) 4) |

Home gardens, parcelas familiares, solares: vegetables, flowers, fruits

Roof production

Pigs |

Grain, vegetables, forage, sheep. pig and poultry |

Intensive use: 800-1000 m_

Extensive use: 0,5-2 ha |

U: Women

Whole family |

|

Lima (Peru)

|

Home gardens, community gardens

|

Vegetables, tubers, trees, hydroponics, herbs, medicinal plants, livestock (PU) |

U: 60 - 200 m_ |

U: Women

PU: Women and Men |

|

Asia |

|

|

|

|

|

Hubli-Dharward (India)

|

Vegetables, small livestock

|

Livestock, vegetables, sewage based Farming System |

PU: 6000 - 8000 m_ |

Vegetables: Women , livestock: men and women |

|

Vientiane City (Laos) |

No information |

Vegetables, |

PU: 5000 m_ |

PU: Women and men |

|

Manila (Philippines)

|

Vegetables, fish, poultry

|

Rice

|

no information

|

U: Women (vegetables)

PU. no information |

|

Cagayan de Oro (Philippines)

|

40 % home gardens/ fish production |

Crops and vegetables/ fish production |

PU: 1,7 ha, 0,5 ha for vegetables |

no information |

|

Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam)

|

No information

|

Crops, vegetables, sugarcane, rubber, gardens, orchards |

no information |

no information |

1) Information on San Jose (Costa Rica) from C. H. Marulanda (personal communication), according to this source, the situation in other major cities of the area, like Managua (Nicaragua), Guatemala (Guatemala), San Salvador (El Salvador) and Bogotá (Colombia) is very similar with respect to sizes of the home gardens and the high involvement of women in vegetable production.

2) Information for Santiago (Dominican Republic) from J. P. del Rosario (personal communication)

3) Information for Port au Prince from M. Regis (personal communication)

4) Information for Mexico City from B. Canabal (personal communication)

5) PU: Peri-Urban

6) U: Urban

The data clearly show that crisis situations on the individual and household level as well as the city level (poverty, unemployment, rapid growth) lead to an increase in informal sector employment which UA is one part of.

4.22 Farming Systems Information

Home gardening is a common feature in urban areas world-wide except for Asia. Nevertheless it appears that household based small scale food production activities are often overlooked.

Open space production of crops and vegetables is most common in African countries, but in a similar way practised in the so called "solares" in Latin America.

Livestock and small animal husbandry is widely spread all over the world's cities.

Studies in the peri-urban sector indicate the more commercial character of peri-urban food production.

Average farm sizes vary greatly. While home gardens by nature occupy small plots of 5 - 400 m_, open spaces are generally > 400 m_ up to one hectare and sometimes even larger. The peri-urban production in Africa is dominated by men, but this seems to be different in Latin America and Asia, where the distribution of work among the family members seems to be more equal.

Home gardens is women's business all over the world. Gender specific differences are not only related to the degree of commercialisation but also to the kind of crops grown. Typically the produce of women's gardens is contributing to household food security and small income generation. Women tend to be more involved in vegetable production and small animal husbandry than men are.

4.2.3 Basic conditions and requirements for urban agriculture

When we compare the information required for the frame (see Figures 1 & 3) it becomes apparent that not enough data can be drawn from the case studies to fully verify the frame. Information is scarce, especially with respect to stakeholder organisation, data on labour markets and income generating employment opportunities. Information gaps exist with respect to city economy and food systems, the cultural background of urban farmers and the quality of land and water.

Especially very little information on capacity of organisations, socio-economic data, access to credits, quality of water and land and degree of self-organisation is available.

The problem of data interpretation is due to the often one-sided information base on urban farming systems. A somehow holistic approach to urban food systems is rarely reflected in the case studies. Therefore we have to be careful with drawing general - world wide - conclusions.

Nevertheless some conclusions that might be of more general validity can be drawn from the studies and the additional statistical data. For the analysis of the economic conditions, data from the World Resource Institute (WRI) was used (WRI 1997, 1999).

In all the cities reported the basic requirements for agriculture are fulfilled. This means the natural conditions allow crop cultivation and/or livestock keeping, physical infrastructure and services are available, at least to a certain extent. The socio-cultural conditions are in favour of farming, at least within a part of the urban population. The institutional conditions provide access to certain resources or do not prevent it and the economic conditions support UA.

Table 3: Basic conditions and requirements for UA*[for more information see Annex 2 & Annex 3])

| |

Region |

| |

Africa |

Latin America |

Asia |

|

Urban Growth |

2.5 — 8 % |

< 1 - 4.5 % |

1.7 - 4.4 % |

|

Economic Situation |

In all the cities the economic situation for the poorer strata of the population is difficult |

|

Availability of Land |

In majority difficult except for Accra, Nairobi and Havana |

|

Access to Land /

Security of Land Tenure |

In most cases it is problematic except for Havana were it is state regulated |

|

Availability and Access to Water |

Only Havana and Cagayan de Oro report favourable water availability, in all other cities it is problematic |

All authors provide information about the basic conditions. However it is left to the individual author to decide on the final assessment of those criteria which do not have a definite value or a precise indicator (such as availability and access to land and water). It has to be kept in mind that availability or access is perceived differently by different urban groups.

4.2.4 Conditions and requirements for improved performance of urban agriculture

There is no information about the soil types and fertility. However, natural hazards (flooding, storms, earthquakes) are reported to be a problem for UA in Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, Lusaka, Havana, Mexico City and the two Philippines cases. This indicates that UA sites in many cities develop on areas subject to hazards and not used for other purposes.

Table 4: Conditions and requirements for improved performance*[for more information see Annex 4])

|

Natural Conditions |

Hazards |

Little information available, only Nairobi, Dar es Salaam and Havana report problems |

| |

Pests & Diseases |

Most cities report either problems or no information is available. Only Havana and Santiago report no problems |

|

Institutional Conditions |

Policy / Legislation |

Policies exist only in Dar es Salaam, Lomé and Havana |

| |

Access to Markets |

Only in Cairo, Accra, Havana and Sofia access to markets is no problem |

|

Physical Infrastructure |

Extension Service |

Extension service is only available in Dar es Salaam, Lomé and Havana |

|

and Services |

Waste Management |

Hardly any integration of waste management into UA |

| |

Inputs, Capital |

Everywhere a problem |

|

Socio-cultural Conditions |

Public Acceptance |

UA receives only full public support in Havana. |

| |

Acceptance of individual property |

Theft is not reported in Harare, Sofia and Santiago, while all other authors mention it as problem |

| |

Degree of Organisation |

No information available |

Pests and diseases are a problem nearly everywhere in Urban Agriculture, except in Havana and Santiago de los Caballeros (Dom. Rep.).

Availability of extension services in Asia seems better organised for the urban/ peri-urban sector as opposed to all the other regions. Also in two African countries (Togo and Tanzania) urban farmers are addressed by extension advice to some extent.

In nearly all cities urban farmers have problems with the availability and/or the access to water. This is a clear indication for missing water infrastructure (water taps, wells). The need for irrigation is more prevalent in countries with lower average rainfall and the more extended dry season.

In spite of the urban waste problem, a systematic integration of waste management is hardly realised in any city. Only from Dakar, Lima, Hubli-Dharwad and Santiago de los Caballeros are first attempts to link urban food production with waste recycling reported.

Inputs and capital for urban agriculture is lacking in all countries, partly caused by high costs as e.g. in Brazil but also by lack of availability.

On socio-cultural conditions there is a general lack of data. The acceptance of individual property rights is low in four African cities where theft is reported to be a major constraint for urban agriculture. The Asian and Latin American case studies do not tackle this problem.

There is no information about the organisational degree of the urban farmers from any of the 20 cities.

In only four of the cases (LomŽ, Dar es Salaam, Havana and Vientiane) are policy and legislation in favour of urban agriculture.

Access to markets is a problem in most African cities, except Accra and Cairo, everywhere in Latin America and Asia (except Havana and Vientiane).

Putting the frame side by side with the case studies and cross-checking the information against the model allows valuable insights:

- in all cities people, especially from the poorer strata of the population, have to struggle for their daily lives. The worsening economic conditions put considerable pressure on them and to make ends meet they have to develop survival strategies - of which UA is one.

- to select UA as a strategy certain basic conditions have to be in place. In all cities people found these conditions - and opted to take up UA as their profession to support their families

- furthermore cities show different degrees of "UA success stories" - depending very much on the enabling or disabling environment the city provides.

- It becomes obvious that despite the considerable amount of literature on UA it remains difficult to compare the situations in the different cities. The frame can be a first step to focus on certain key factors and to arrive at a decision whether support of UA is a valid option for a city.

5 Supporting UA - planning for interventions?

5.1 The areas of intervention

How to initiate the promotion of UA? We want to make proposals how Urban Agriculture can be promoted and interventions placed. Depending on the combination and prominence of basic and supporting factors in a given city environment and the existence of interested stakeholders the entry points for interventions can and will be different. Three "areas" are of major interest.

Research, formal or informal, will provide data for decision making as well as technical solutions. Policy incorporates decision making processes on all levels with an impact on UA. Action stands for all activities undertaken by and together with urban farmers to improve their situation.

Usually a temporal sequence regarding the interaction between the three areas can be observed as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The phenomena Urban Agriculture and its temporal sequence Not included here.

Looking at a time line the three areas get involved in Urban Agriculture at different points :

1. The Phenomenon

It all starts with what we call the phenomenon of Urban Agriculture. People chose UA as an activity (for several reasons). UA activities at this point are more or less informal and individually organised, mostly low - profile.

2. Research gets interested

The scientific community gets attracted and starts research work on selected topics. In the forefront one can find baseline surveys and a more "descriptive" type of research. The information is initially scattered, it reflects personal interests of individual researchers but gets more complex with time.

3. Policy makers start to react

An increasing number of urban farmers, growing exposure by researchers and more information can finally raise the awareness of the general public including decision makers in the city. The reactions of the latter range from ignorance to preventative measures or to support.

4. Action is complementing the informal efforts of the urban farmers

Support or Action can start any time on a small - scale (e.g. small community projects, components in community programmes).

There is still little experience of a larger-scale co-ordinated initiative on city level in the recent past (on example is Havana, Cuba). Some action is taken here and there but no co-ordinated efforts are initiated. The political will and guidance, which is required for a large scale city-wide action, is missing. UA remains what it always was: an informal business, hindered in some areas, maybe supported in others but without exhausting the full potential to the benefit of all urban residents.

An ideal situation requires that stakeholders are identified and each one is given its role, clearly defined with tasks and mandates, under the conditions to co-operate, share experience and exchange information. It has to be kept in mind that all activities have to be geared towards improvement of the living conditions of the urban environment and its people, the needs of the urban residents have to be the driving force.

5.2 Roles and functions within the intervention areas

Co-ordination among different actors on various levels and from different sectors is essential if urban agriculture should be more than an informal and individual activity. Effective promotion of urban agriculture needs one leading stakeholder in one of the three sectors with the mandate to guide the other necessary players. In most cases the co-ordination function will lie with the policy level or has at least to be delegated by policy makers. Research can catalyse activities but is seen mainly as a support for the other pillars. The following pages will highlight possible actors and the tasks, which would fall under their responsibility.

5.21 Research

Research has the function to contribute the necessary information for decision-makers and implementers as a base for discussion (awareness creation), decision making and to prepare the way for interventions with other actors (IDRC 1999a). The challenge for research will be to leave the ivory tower and to support the development of applicable strategies by or together with the communities. Capacity development is a field where research institutions have a mandate (Sawio & Spies 1999). All this makes research an indispensable and welcomed co-operating partner.

Possible stakeholders:

| Universities/ Colleges | Research Projects or projects with research activities |

| Research institutes | NGOs/ CBOs with research activities |

| Research units of line Ministries | Individuals |

Main tasks:

Provide information about the potential of Urban Agriculture activities in a given city with regard to the main objectives food security, income generation and city ecology

- with involvement of the urban farmers

- for decision makers and implementers

Information could cover

- Description and assessment of the basic and supporting factors inducing UA

- Description of prevailing Urban Agriculture activities

- Assessment of the contribution of Urban Agriculture with regard to social, economic and environmental aspects towards a defined objective (e.g. food security)

- Institutional framework in a given city

- Target group differentiation and their motivation with an explicit focus on gender aspects

Create awareness and about UA in various aspects on all levels (lobbying)

Facilitation of concepts for

·

- the integration of Urban Agriculture in sustainable city development

- practical initiatives as direct support to urban farmers

together with primary and secondary stakeholders

- Act as adviser to policy makers based on available information and research findings

- Share and exchange experiences with other national and international bodies and individuals

5.22 Policy

While research is seen as an entry point for the discussion about UA and possible interventions, the political level is essential to guide the activity, make it acceptable and therefore formal (institutionalisation) and give the mandate for its promotion or restriction. The co-ordinating function lies with the policy level. In cases where a strong institution exists in the research or action area, policy can charge it with the co-ordination function.

It has to be assured that stakeholder identification is a continuos process and newly emerging institutions/ groups are accommodated. The co-ordinating body should also encourage activities in research and action and take up responsibilities for funding1 [Funds have to be available for research, policy and action. The "policy level" is usually in charge of the local budgets. Limited local budgets can be supplemented with contributions from the communities themselves and in most cases have to be complemented by external funds. Acquisition of funds/ resources is therefore a task in all areas.].

The co-ordinating body should ensure that all stakeholders adhere to the principles of community participation (laid down in the Local Agenda 21). UA, even so sometimes labelled differently (e.g. natural resource management) might be one issue for the communities. Since self organisation of people is essential for any activity in one of the areas, supporting UA will have an impact on, democratisation, civil society and sustainable city development.

Possible stakeholders:

| Local Governments | Local Community Leaders |

| City Councils | Community Groups |

| Line Ministries (e.g. Agriculture, Land, Water) | Individuals |

| Members of Parliament | |

General task for policy makers involved in city development

Establish planning, implementation and feedback mechanisms between policy level and communities for efficient participation to steer development

Main tasks with regard to Urban Agriculture

- Set in place and institutionalise mechanisms for effective co-ordination of Urban Agriculture activities (co-ordination)

- Define lead stakeholder for co-ordination and get agreement from all stakeholders about the mandate

- Provide a legal framework for Urban Agriculture activities (Quon 1999)

- Regulating access to land and water

- Defining environmental standards for Urban Agriculture

- Institutionalise administrative procedures (with focus on the community level) to get access to the above mentioned resources

- Institutionalise procedure to monitor positive and negative effects of Urban Agriculture with regard to social, economic and environmental conditions and define responsible bodies

- Establish procedure to oversee law enforcement on issues regarding Urban Agriculture

5.23 Action

Urban Agriculture is practised even before any practical support. Usually this is done on a rather individualistic basis, most often in the twilight between legality and illegality. Services and support are not available, but also not expected. Farmers do not adhere to rules and regulations, e.g. use of potentially contaminated irrigation water and unhealthy plant protection measures do occur. The situation changes when the farmers articulate their demand or policy makers or implementers get attracted to UA.

In order to become a respected partner in discussions, practitioners have to get organised. They have to develop a vision for their activity otherwise strategies developed by researchers or policy makers will be forced on them. They have to learn to air their demand for government services but also take up their duties as urban residents and members of a community (cope with the negative effects of UA). This transformation of an informal activity in the shade, towards a respected employment opportunity, can be facilitated by the action level and finally get support from policy makers.

Possible stakeholders:

| Government staff on target group/ grass-root level | Private sector |

| NGOs/ CBOs | Religious groups |

| Projects (donors) | Interested Individuals |

| Urban communities | |

Main tasks:

The Action intervention comprises of two different sub-sectors Facilitation & Education and Technical Support.

Facilitation

- Awareness creation about the role and potential of Urban Agriculture on a community level for the individual household

- Make known procedures to access resources and support mechanisms to practise Urban Agriculture

- Organisational support to communities

- Support application of planning and decision-making procedures to steer sustainable community development, including Urban Agriculture

- Facilitate feedback about needs and demands with regard to Urban Agriculture

- Create awareness about the environmental implications of Urban Agriculture

Technical Support

- · Provide or make available services to the communities and its members Through development workers and extensionists

- Group strengthening/ organisational support to producer groups

- Technical extension service

- Legal advise and support mechanisms

- Marketing information

- Financial support opportunities

- · Facilitate implementation of UA legislation (support as well as law enforcement) by communities

- · Support communities to monitor UA activities, especially environmental aspects

5.3 Cross-cutting Issues

There are a number of issues which are reflected in all three areas. They will be jointly addressed in this chapter.

Getting started

One major assumption in our model is that someone or somebody always starts the initial steps, no matter in which of the three main areas. Experience shows that it happens, particularly in the areas of research and action. It can be one research institute, a NGO or a bi- or multilateral project, even an individual who gets attracted by the phenomenon of UA.

The problem usually is experienced within policy. Political acknowledgement and guidance makes the difference between Urban Agriculture as an informal, low-profile and often illegal activity and an accepted and supported intervention. Policy makers tend to react rather than act, especially in developing countries where problems overwhelm the capacity of the administration. Urban Agriculture is hardly a priority aspect on the agenda, but one potential option among many. Therefore it is very haphazard, which institution in the area of policy starts working on UA. If the co-ordinating body is unsuitable, but not willing to delegate the mandate for the promotion of UA, effective support becomes very difficult. However, to achieve impact this has to be tackled.

Gender has not been mentioned as a separate condition for the occurrence of urban food production because both men and women practice Urban Agriculture. It is not intended to neglect the importance of gender. Gender is seen as a cross-cutting issue and is of major importance in planning and implementation of interventions in Urban Agriculture. Gender differences, e.g. gender specific access to resources or gender specific participation in planning and decision-making processes does influence the appearance of certain forms of urban food production (Jacobi & Amend 1997). By and large men are more prominent in economic production while women are more related to household food production (see city case studies). Any intervention has to consider those aspects.

Monitoring and Evaluation

For the successful implementation of support measures a functioning Monitoring and Evaluation system (M&E) is required. The activity appears several times in the model and again here it is emphasised.

There is a need to agree on indicators of success; who will do the monitoring of these indicators and what kind of effects the results of regular evaluations will have. Especially for the over-all monitoring the consent and co-operation of all stakeholders (primary and secondary) is crucial. In case external funding is sought this is even a precondition for eligibility

5.4 The Urban Agriculture Flow Chart

The flow chart visualises the above roles and responsibilities, shows linkages within the areas and brings the activities in a logical sequence . All the activities are on an aggregated level, a simple task might in reality take weeks or months to be implemented. The flow chart shows an "ideal" situation and looks primarily on UA. In an urban environment UA activities will be combined with other tasks and not appear as a single activity.

The flow chart is based on several assumptions:

- Conditions for UA are favourable

- Support to UA is an economic prevention measure against urban poverty

- Stakeholders have decided to support UA

- The research community is going to take up the topic

- Service providers can be identified and will offer services demanded by the target group

The flow chart is meant as a guideline for interventions by interested stakeholders in one of the three fields. For us, there are a few guiding principles with regard to co-operation and linkages. We feel it is essential that there is:

- Close linkages between research, policy and action

- Co-ordination of all activities on all levels inter-sectoral and cross-sectoral

- Linking of urban agriculture activities with other areas of sustainable city development (e.g. waste management, informal sector promotion)

There is sufficient experience of interventions, often successful on their own, specifically targeting one of the areas. However it is felt that only the combination of activities from different areas can bring considerable changes *[Plenty of valuable research is available, but not considered by policy makers, well elaborated city development plans and city bye-laws exist, but they are not efficiently enforced, community initiatives are successful within their boundaries, but not replicable to other communities in the city.]).

Figure 6 Urban Agriculture Interventions Not included here.

6 Urban Agriculture in the current development discussion and recent initiatives

Where does UA fit into the mainstream development policies? We try to place "support to UA" in the wider context of development and indicate where UA can be integrated. We are of the opinion that promotion of UA should not be seen as an objective by itself. We understand it rather as a promising tool to contribute to a variety of development goals and with great potential to link it with other urban development issues.

Sustainable development, poverty alleviation, food security and environment and natural resource management are common mainstream development policies.

There are plenty of statements from many governments world-wide and both multi- and bilateral agencies who make poverty alleviation their main concern and the poor their primary target group.

The World Food Programme (WFP) identifies its target group in a paper called "Enabling Development":

The hungry live in rural areas and urban slums. Hunger is entrenched in areas of concentrated poverty, resource degradation and recurrent food shocks, and among people who are marginalised from mainstream development. Wherever they live, women and children, especially girls, are disproportionately represented among the poor and hungry. WFP«s new policy directions strengthen an enabling environment for poverty alleviation by:

- Targeting the poorest countries, and marginalised people within those countries;

- Continuing to meet the special needs of expectant and nursing mothers and young children to prevent hunger from being passed from one generation on to the next;

- Seeking partners who are also committed to assisting the very poor, and can provide development opportunities to link with WFP interventions;

- Building on the Commitments to Women made in Beijing - especially by placing food in the hands of women which better benefits the household, especially children, and is potentially empowering for women; and

- Making more use of participatory approaches to involve communities in the selection and design of activities, and to better reach the very vulnerable in a community (WFP, 1999).

The German Ministry for Development Co-operation (BMZ) states:

Poverty is one of the menaces which are no respecter of borders and have developed into global dangers. Other threats, which to a certain extent are associated with poverty and jeopardise the survival of mankind, are increasing environmental destruction, climate change, the loss of biodiversity, rapid population growth, the spread of epidemics, natural disasters, wars, refugee movement and drug production.

It is the shared responsibility of all states to find an answer to these global challenges. When development co-operation addresses these threats and attempts to combat their causes, it is assuming a task which lies in our long-term interest. German development co-operation therefore contributes to securing our future and is in line with the goal formulated at world conferences held over the last few years of enhancing the level of human security world-wide. German development co-operation has therefore identified three priority areas: poverty alleviation, environmental and resource protection and education and training. Measures in these priority areas are most suited to the ideal of sustainable development which describes economic, social and ecological development as an indivisible unit (BMZ 1999)

Still, it is probably fair to say that arguing on this rather "abstract" level will not convince decision makers and planners to suddenly turn to urban agriculture. A field, closer related to UA, is the discussion about Agenda 21 and specifically the initiative of Localising Agenda 21.

Background: Local Agenda 21

Urban development coupled with scarcity of resources often accelerates environmental degradation, leading to loss of quality of urban living conditions, especially for the urban poor. There is an increasing awareness about the urgent need to harmonise urban development with environmental protection. Agenda 21, the blueprint for Sustainable Development resulting from the Earth Summit (Rio de Janeiro, 1992), recognises that many of the problems and solutions concerning sustainable urban development have their roots in local activities.

Local authorities construct, operate and maintain economic, social and environmental infrastructure, oversee planning processes, establish local environmental policies and regulations. Operating at the level of government closest to the people, they play a vital role in informing, mobilising and responding to the public to promote sustainable urban development. The participation and co-operation of local authorities is a primary determining factor to fulfil Agenda 21 activities at the local level.

In Chapter 28 of Agenda 21, local authorities in each country are therefore called upon to undertake consultative processes with their population in order to achieve a consensus on "local Agenda 21" for their community. The Habitat Agenda (Istanbul, 1996) reconfirms the local Agenda 21 framework as a valuable approach to harmonise urban development and the environment.

(Localising Agenda 21, UNCHS (Habitat), 1997)

The concept of urban agriculture as promoted by the international scientific community is not very well known in many developing countries (Gertel & Samir 1999, Drescher & Muwowo 1999). Most people producing food in the cities would not recognise their own activity as being "urban agriculture", and would probably have considerable difficulties in bringing their individual struggle for food or income in relation with mainstream development policies. The label "Urban Agriculture" is somehow problematic as "agriculture" is still associated with the rural area and has in many cases the image of being backwards backward and therefore unwanted in cities.

We can only encourage decision - makers and planners to look at "Urban Agriculture" in a more open and flexible way and to identify it's potential without being caught in terminology and narrow definitions.

In the communities urban agriculture is practised however, few initiatives world-wide aim at the holistic promotion of UA as a core objective. Urban food production can and should be linked with a variety of initiatives, not only agriculture - oriented. Urban agriculture might be a "hidden" activity within a wider programme. It is not our aim to "claim" all activities as UA, but by looking at it in various contexts we want to show that it can become an interesting option for many, both on a national and international level.

Table 5: Possible areas for the integration of urban agriculture as an intervention

|

Urban development |

- Support programmes to City Authorities (Town planning)

|

|

Environment/

city ecology |

- Waste management and nutrient recycling

- Microclimate improvement

- Soil conservation

- Water management

- Bio-diversity

|

|

Health and Nutrition |

- Household food-security

- Mother and child programmes (nutritional programmes)

|

|

Small-scale business promotion/ Vocational training

|

- UA as an income opportunity for producers, and secondary small scale enterprises (input suppliers for agricultural production, retail sellers etc.)

- UA as one option for vocational training

- Credit programme, UA being one option eligible for credit

|

|

Community development;

Capacity- building/

Self-organisation and self-help initiatives |

- Capacity building for local initiatives

- Improve the creation of sustainable communities (management of own initiatives, steering community development on grass-root level)

|

|

Education |

- Environmental awareness, UA as a way to bring urban people closer to nature and natural resources

- School garden initiatives

|

|

Youth and Women development |

- UA as an opportunity to generate income, provide food for the household and gain social status within the family or community

|

Urban Agriculture as a phenomenon has been persistent over the last years in many cities throughout the world. Considerable efforts from research institutions, committed individuals coupled with promotional programs and projects in the 1970s and 1980s have finally guided the concept of UA into the development arena. It would be a challenging task to give a comprehensive overview of all the actors and institutions supporting UA. Bi- and multilateral agencies, research institutions, NGOs and individuals have been and are supporting UA (UNDP, WB, EU, GTZ, CIDA, DANIDA, SIDA, and many others). Only a few of the ongoing programmes and recent initiatives are highlighted as examples.

Major players in urban development - UNEP/UNDP/HABITAT/the Urban Management Programme (UMP) and the Sustainable Cities Programme (SCP) recently started to consider and integrate urban food security in its programmes, e.g. through integrated waste management approaches, city planning guidelines, market development. More co-operation is seen in this field in some countries.

The Urban Management Program for Latin America and the Caribbean (UMP-LAC), currently in its third phase (1997-1999 or 2001), is carrying out City Consultations with interested local governments and civil society actors. The thematic emphasis for the consultations is threefold: urban poverty alleviation, urban environmental management, and participatory urban governance, each with special attention to the issue of gender.

The Regional Office has established contacts with dozens of Latin American municipalities and a wide range of institutions in order to promote city consultations, construct plans of action, and exchange information and experiences on different topics related to urban management and the primary themes of UMP.

The project will have a group of selected resource and associate cities to document a series of best practices and interact in a city consultation, for the formulation of an action plan and specific projects in urban agriculture. The cities will represent a range of city sizes, ecosystems and sub regions. The project will facilitate a formal interaction between regional networks of experts in urban agriculture and of local authorities interested in sharing experiences or in phasing urban agriculture activities into local agenda to better address urban poverty, food insecurity, unemployment, gender inequity, environmental degradation and rural-urban tensions. Results will be edited, published and disseminated to municipal urban actors and others throughout the Region (Excerpt from IDRC 1999)

Participation in urban agricultural activities by key agencies such as FAO was granted through decisions made by the Committee of Agriculture (COAG) in early 1999. An official interdisciplinary, cross departmental working group on urban food security (Food for Cities) was founded in FAO in late 1999. FAO is currently supporting workshops with local authorities in cities of the South (e.g. in Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic) in March 2000. FAO is planning the implementation of pilot sites for Urban Agriculture in 30 cities in developing countries.

Comments of the FAO Secretariat to COAG

"Urban and peri-urban agriculture are growing phenomena in most cities and a great deal of activity goes undocumented and unmonitored. The current knowledge base about UPA is growing but fundamental gaps include: how to define UPA; what are the linkages and complementarities between rural, peri-urban and urban production; how affordable it is compared to alternative food sources; and the full range of impacts, including economic, social, and environ-mental. A comprehensive and sustained effort at data collection is needed to fully comprehend the possibilities posed by UPA." (FAO-COAG 1999, Emphasis added by Drescher & Iaquinta 1999).